A Chat with Nadine Strossen : A Conversation with First Amendment expert Nadine Strossen

“More speech is the best counter to hate speech”

By Charles J. Mays, Political Science Ph.D. student and Graduate Fellow for the University of Delaware’s Center for Political Communication.

On March 14?15, 2019, the University of Delaware hosted “Speech Limits in Public Life: At the Intersection of Free Speech and Hate.” The conference featured former neo-Nazi extremist Christian Picciolini, legal scholars including Nadine Strossen, as well as students and social scientists. Read the UDaily story to learn more about the conference.

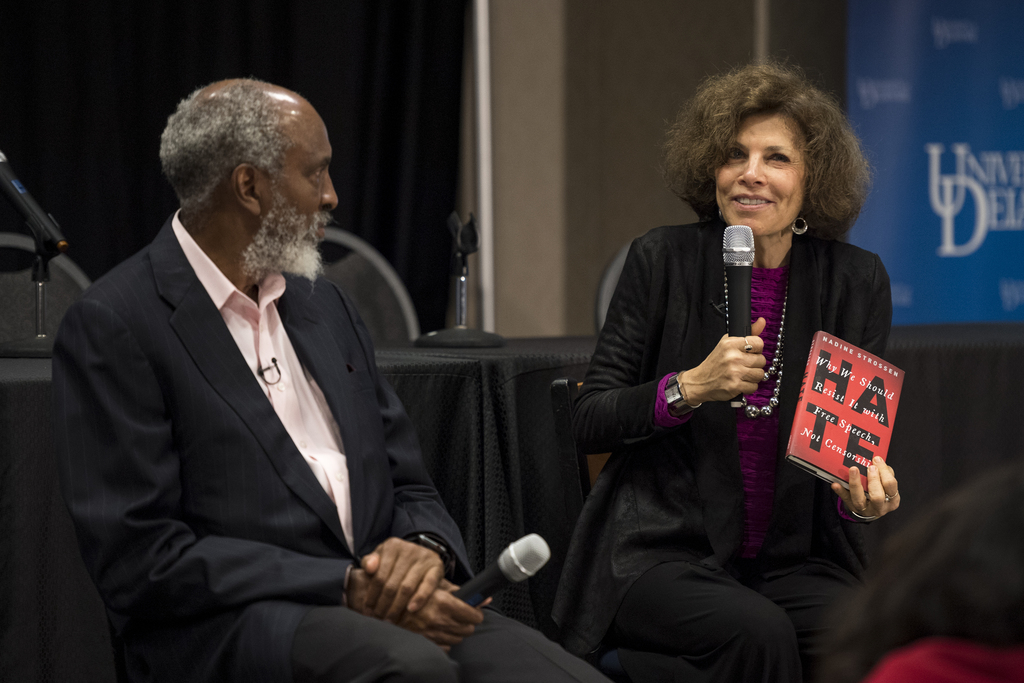

CHARLES J. MAYS: On March 12, a couple of days before the conference, Professor Nadine Strossen discussed her thoughts on hate speech and how best to combat hateful speech while protecting the First Amendment rights of everyone involved. The former American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) president is a Marshall Harlan II Professor of Law at New York Law School and was previously named one of the most influential lawyers by the National Law Journal. She described her passion for civil rights law and her take on current issues in the United States.

NADINE STROSSEN: I’m excited to participate in what is such an impressive conference and in particular I’m excited to be on conversation with my longtime friend john a. powell. I feel very strongly based”let me strike the word feeI”I have concluded, firmly based on an examination of evidence about how censoring hate speech has operated around the world and in the past in the United States, which has reaffirmed a conclusion that I had reached in the past. That is despite the good intentions behind calls to censor hate speech (namely to promote diversity and equality and dignity and inclusivity as well as societal harmony and individual mental well-being). I strongly support all of those goals, but censoring hate speech does more harm than good for those very goals. The most effective way to promote all of them”to promote human rights”is through more speech, not less.

MAYS: I’m always curious how people ended up where they are, you know what led them to take the career path they did. You have been a towering figure in the world of civil rights law. Was there a person or event in your life that lead you to become a civil rights attorney?

STROSSEN: Given my inclinations I was very much focused on and aware of injustices that both of my parents had endured and that other relatives such as grandparents had endured, by virtue of being persecuted members of minority groups”both on the basis of religion and ethnicity but also on the basis of opinions and beliefs.

I was horrified by the fact that my father was imprisoned in a slave labor camp in Nazi Germany for his anti-Hitler activism and because one of his parents was Jewish. And both of those reasons were enough to – conscript him to the most arduous, horrific, brutual slave labor from which he almost died. My grandfather on my mother’s side was an immigrant to the U.S. for economic reasons and he had very dissident political views. He was Marxist at a time when it was considered almost treasonous and he was also a conscientious objector in World War I. For those two reasons he was actually sentenced as a criminal. And the ACLU”which I headed, ironically”was founded at this time to help people like my grandfather. His sentence was to stand outside the courthouse with his hands and feet splayed so passersby could spit on him. But 15,000 people were imprisoned around that time for voicing their objections to WWI and U.S. participation in the war. When I got a little older, the civil rights movement was kicking into full gear in this country and I watched with horror the brutal beatings that were going on – so I was constantly aware of injustice and very eager to counter it in anyway feasible.

MAYS: I went to school in the United Kingdom, and many student union groups and universities have adopted positions of “deplatforming” speakers or groups they deemed to incite hate speech, etc. Do you think we are looking at the same phenomena happening here? Or is the struggle more over security issues stemming from protests?

STROSSEN: Well there definitely have been what we have been calling “disinvitations” that have either been effective or have caused a lot of turmoil, in some cases pressuring the invited speaker to “voluntarily withdraw.” Although I doubt that it was really voluntary because of not wanting to be subject to disruption or harassment. I’m not sure of the exact number of these instances in the U.S., but even one would be too many. That being said, that could just be the tip of the iceberg because we may never know how many invitations were never extended in the first place because of concern that the speaker’s ideas are provocative and will be controversial and will be attacked by certain students.

MAYS: Looking at a specific example of hate speech, I went to the University of Oklahoma for my undergrad and over the past couple of years we have had two separate big incidents where [content about] students has gone viral online for using racist language. From what I understand those students were expelled for violating the student code of conduct. So how would you respond to that as a civil rights attorney?

STROSSEN: Well, there have been several incidents and to the best of my knowledge (I’ve followed the stories as best I can but maybe you know more), there was one incident where the students were expelled or maybe one or more of the students “voluntarily withdrew.” But in the incident where the students were members of a fraternity on a bus and they were singing a racist song, to the best of my recollection. they were expelled.

MAYS: Yes.

STROSSEN: … And that to me is completely inconsistent with their First Amendment rights. To the best of my knowledge every other expert who looked at that situation also said it did violate their free speech rights. They may have chosen not to challenge it because they were embarrassed and didn’t want to be in the limelight but I am confident if they had challenged that expulsion they would’ve won. The more recent incidents that I recall were incidents of “blackface” where one was online and the other was somebody in person. And my understanding is that the president of the university condemned the expression, but said that this is protected speech and made no effort to expel them. And the president was then subjected to massive demonstrations by students who were imposing pressure for expulsion and also saying the president should be forced out because he was not sufficiently taking a strong position against racism. But that was exactly the right call in terms of First Amendment rights. The president was exactly right to say that this expression was squarely at odds with the values of the university and he had the appropriate response.

MAYS: But then how would you respond to someone who made the argument that by being a student and agreeing to a student code of conduct they are sort of entering into a contract of sorts where they are agreeing to uphold values of equality, etc. So when they do violate that code of conduct, that’s ultimately grounds for their expulsion?

STROSSEN: Well I’m sure the student code of conduct [of a public university] also contains pledges of respect for free speech. And in any event we have the supremacy clause of the constitution which makes the constitution supreme over any other law or contractual obligation brought by a state agency.

The basic principle is that the government or a public entity like a public university may not discriminate on the basis of the viewpoints, the idea, the content of speech. It may only punish speech if you get beyond the content, i.e., “We hate that message” or “It’s offensive.” Those are purely content-based judgements that are impermissible. If the government dislikes an idea, its recourse is to counter with refutation, with condemnation, or debate, but not with censorship. Government may only censor speech or punish speech whether its online or in any other context in what’s called an emergency situation where the speech directly causes certain direct and specific imminent harm where the only way to prevent the harm is through censorship.

The Supreme Court has recognized a number of subcategories of speech that does fit that principle, such as the intentional incitement of violence where the speaker intends the violence to occur imminently. Another example of an emergency situation would be where speech constitutes what lawyers would call a “true threat” where the speaker is addressing a discrete group of people, small group of people, and intends to instill in them a reasonable sense of fear that they will be attacked. A good example of that would be Charlottesville when the demonstrators were expressing their vile, obnoxious words, which are constitutionally protected. But when you get beyond that and look at the context”they were marching en masse with torches that are lighted and brandishing firearms”I think that would’ve satisfied the true threat standard and could be punished.

MAYS: Lastly I’m curious as to where you see freedom of speech under threat outside universities? Do any particular policies or does the rhetoric of our politicians concern you?

STROSSEN: The rhetoric among politicians is terrible. I mean starting with the commander in chief setting a terrible example and emboldening opponents of free speech around the world. I follow the developments in media from different countries, and the worst dictators and authoritarian leaders are literally quoting Donald Trump in calling the press the “enemy of the people.” Let me be clear however. He of course has a free speech right to criticize the media and to do so in very harsh terms, if that is his prerogative. But we have to be very careful when we’re talking about someone in such a position of power, especially when he goes beyond mere criticism to threaten actual regulatory action against the press, which he has done.

A free speech and literary organization has brought a lawsuit against Trump last fall, arguing that he had actually violated their First Amendment rights by threatening to withdraw broadcast licenses from certain TV stations and networks unfavorable to him. And he threated to oppose mergers because he didn’t like the perspectives the networks were taking on his policies. And he has denied press credentials or revoked security clearances of critics who have used the media to express dissent toward some of his policies.

Not only Trump, other politicians all over the country at every level of government have also kicked people off their social media platforms when people criticized their policies. We have a lot of lawsuits now, with the vast majority saying these actions violate the First Amendment. When officials use these [platforms] to engage with constituents, they can’t selectively kick people out.

I’m also very concerned about the attacks on people who are taking the knee in protest of racial justice, athletes and others. They have been threatened and intimidated and in some cases public schools have punished students who have done that, exercising their First Amendment right to protest.

I think those are the major problems, but I do want to also say that the recent developments with social media is a whole separate can of worms in terms of enforcing their own community standards. They are not bound by the First Amendment. They are exercising their own First Amendment rights, but from a practice purpose they have real censorial power in today’s media landscape and they are exercising it in ways that are arbitrary at best and discriminatory at worst.

MAYS: I’ve had these conversations recently with a friend who mentioned he thinks social media should be regulated as a public utility.

STROSSEN: It’s a very difficult issue for me as a civil libertarian because I have to ask, it really comes down to, what is the lesser of two evils? Who do I distrust more? The big brother government? I certainly don’t like the way the government has used its regulatory power in the past such as the fairness doctrine where Presidents pressured the FCC against media outlets that were hostile to the president’s own policies. And Trump is following in a long line of predecessors in that regard. On the other hand do I trust the bros of Silicon Valley any more than I trust or distrust the government? It’s a very difficult issue for me.