Fake News Blues : Fake News Blues: Trust in an Alternative Facts World

Communication experts say public must take responsibility

Article by the Center for Political Communication, April 4, 2017. For resources associated with the talk, please visit the University of Delaware Library’s Busting Fake News web page and the University of Delaware Journalism Program’s presentation. See the entire conversation here. Read and download the transcript.

In an era of broad distrust, communication experts told a packed audience at the University of Delaware on Monday night that the public must be careful consumers of information. The changing landscape of the media has generated an unprecedented volume of what is now commonly called fake news. While sitting in front of a large image of Time magazine’s “Is Truth Dead?? cover (April 2017) panelist Nichole Dobo observed, “It is up to the public to hold journalists responsible.” Dobo is a staff writer and social media editor at the Hechinger Report.

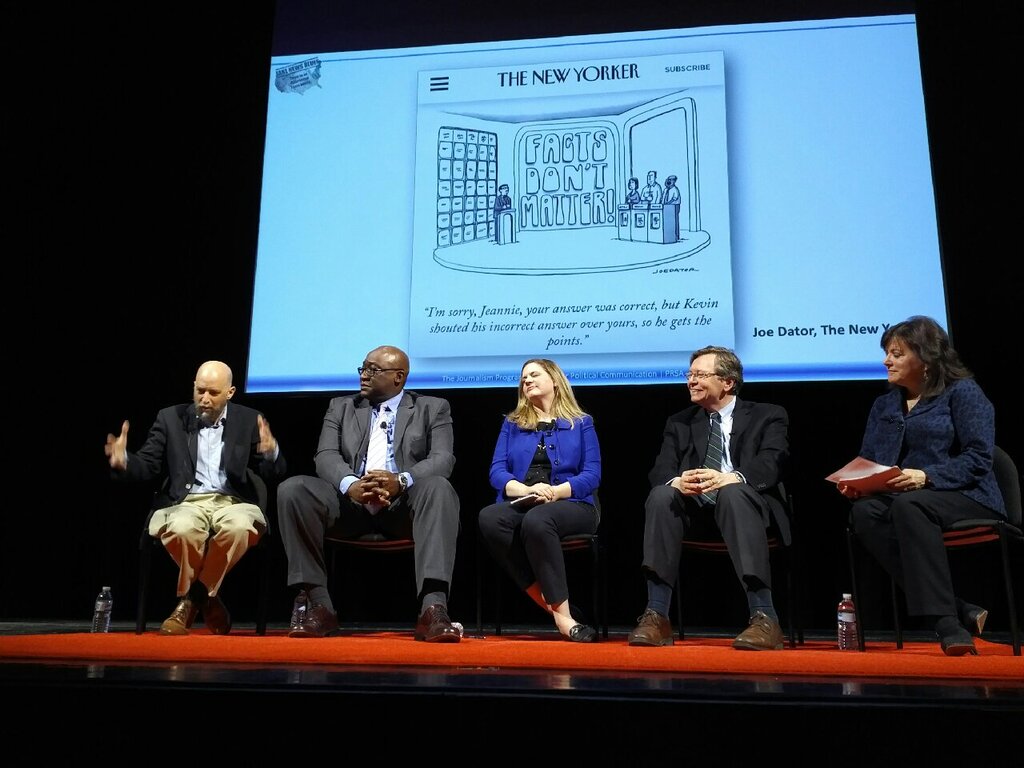

UD Journalism Program Director Deborah Gump told the audience that fake news isn’t a new phenomenon, but it has proliferated in recent years. The traction of recent “fake? headlines, such as “Mexican drug lord “El Chapo? breaks out of prison for third time? and “United States revokes Scientology’s tax-exempt status,” demonstrates a need to educate the public about media literacy. Gump partnered with Public Relations Society of America (PRSA) Delaware Chapter and the Center for Political Communication (CPC) to host the April 3 event at Mitchell Hall. CPC Director Nancy Karibjanian moderated the panel discussion.

Information overload and a call for media literacy

Panelist and UD alumnus Charles Lewis (AS ?75) said that journalism has a long history of misleading the public, but the difference now is sheer volume. Lewis is a professor and founding executive editor of the Investigative Reporting Workshop at the American University School of Communication in Washington, D.C.

Social media brought the fake news phenomenon to the forefront during the 2016 presidential election, with 38 million false election-related stories shared on Facebook in the final 3 months of the campaign, according to a January 2017 Stanford study. On Donald Trump’s social media power during the presidential race, News Journal editorial page editor Jason Levine said, “Donald Trump was just louder. We have a personality that has sunk his teeth into the social media fabric.”

Information overload complicates the problem. Levine said, “We are facing a torrent of information. We used to be standing under a leaking ceiling, but now we are standing under Niagara Falls. It is a huge, constant, 24/7 flow of information. People are overexposed.”

Young people aren’t equipped to identify fake news, according to Dobo. “A Stanford University study [November 2016] reported that 93 percent of college students couldn’t flag [content from] a lobbyist’s website as biased information. We need to teach students critical thinking skills.” Leon Tucker, communications director for the Delaware Department of Labor with 20 years of experience in journalism, added, “We miss an opportunity as journalists to educate the public about the importance and meaning of journalism. You would be surprised at how many people believe that the opinion page of a newspaper is news.”

Experts in the audience shared their insights on the need for better education and ethics in journalism. Leigh Weldin, a high school civics and economics teacher in Wilmington, Delaware, spoke about the need for media literacy education for both students and parents. UD librarian Lauren Wallis said that increased interest in the issue of fake news prompted the UD Library to publish a “Busting Fake News? page on its website: http://guides.lib.udel.edu/fake_news. Jerrod Bates, a digital forensics expert with Delaware Technical Community College, said that it is possible to manipulate public opinion with bots, the process of renting tens of thousands of computers to like a story or post.

On living in the era of a post-truth society, Lewis said, “We need to keep eternal vigilance of the media. We can do that through literacy.” Leah Weldin is on the front line of the media literacy challenge. “I help students identify propaganda. Everything is a shade of gray, so claims in media that it’s this and nothing else should be questioned. I want my kids to be comfortable with being uncomfortable.”

The event was hosted by University of Delaware’s Journalism Program and the Center for Political Communication, in partnership with the Public Relations Society of America (PRSA) Delaware Chapter.